Wednesday, February 16, 2022

Friday, February 11, 2022

HW for Feb. 15: Gary Snyder, "Unnatural Writing" (59-68) + "Nature"

Answer to one or more of the following:

1. Why the title?

2. There are some passages of "Unnatural Writing" that may be read as implicit comments on Emerson's "Nature". Comment on possible points of (dis)agreement between Emerson and Snyder.

3. Which of Snyder's recommendations for a "New Nature Writing" most intrigue you and why.

Thursday, February 3, 2022

HW for Feb 8 - R. Waldo Emerson, "Nature" (anthology, pp. 34-54)

Choose one of the following two reading suggestions to expand on:

1) Recall what you learnt in your Philosophy classes in Secondary School about Immanuel Kant's Criticism of Pure Reason and his concept of Transcendental Knowledge (this post in another blog may refresh your memory, http://euliteratura.blogspot.pt/2016/10/the-copernican-revolution-in-knowledge.html) and explain how his ideas illuminate certain passages of Emerson's text.

2) Considering that the essay was written in 1836, what aspect(s) do you think were novel in Emerson's conception of Nature? What about today? Which. are novel and which may be problematic?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

HW for May 19 - Telling Stories about Ecology (anthology, pp. 251-258)

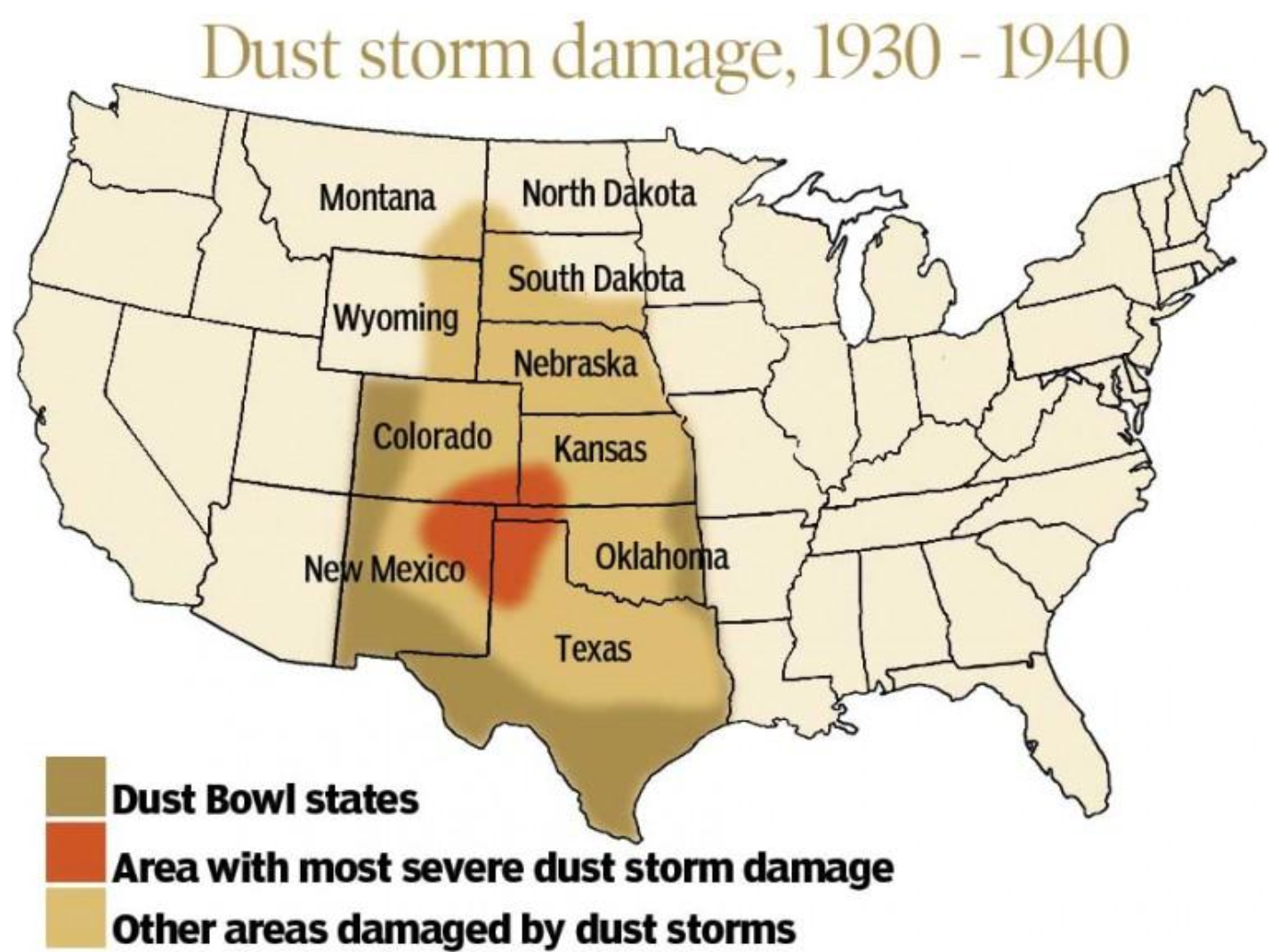

In the article "Telling Stories about Ecology", William Cronon commnents on the history of "the Plains' States" (in...

-

Annotated bibliography - where you reference and explain briefly two sources that you plan to use - ONE at least has to be a scholarly arti...

-

Answer to either or both: 1. Compare/contrast the two excertps, in light of the concepts of "border", "im/migration" and...

-

In the article "Telling Stories about Ecology", William Cronon commnents on the history of "the Plains' States" (in...